Europe’s Shmoral Shmazard

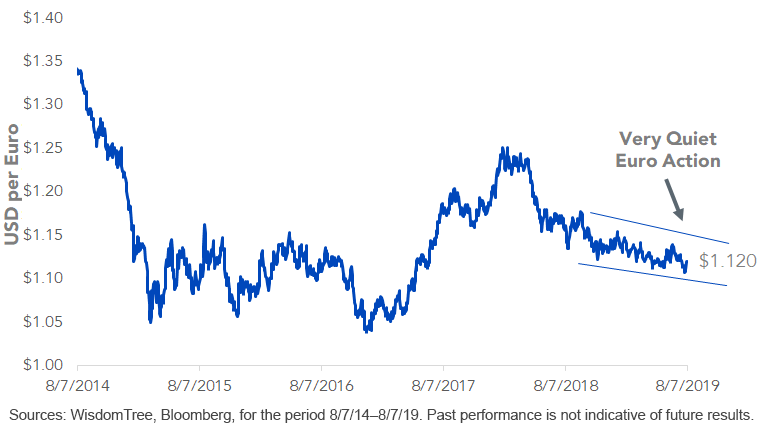

The euro won’t stop chopping sideways. Its quiet drift downward has persisted since spring 2018, but it would be a fool’s errand to extrapolate boring action forever. The currency can snap violently, and I think the push will be southward.

Figure 1: EURUSD

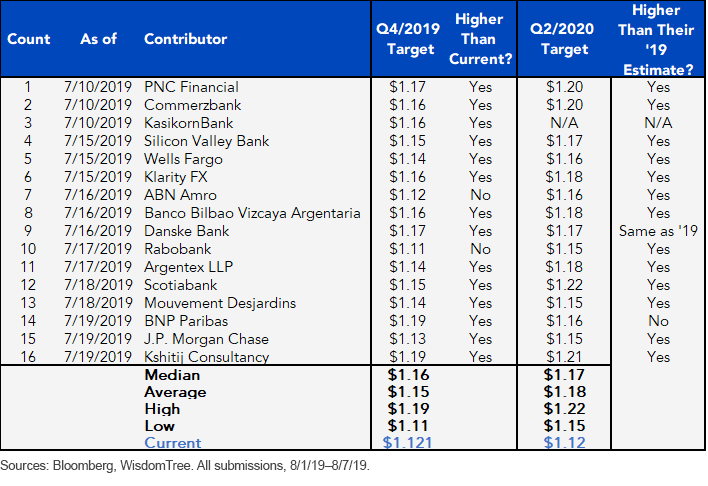

There were 17 euro/U.S. dollar forecasts submitted to Bloomberg since August 1 (figure 2). Notice that though the firms represented here have mixed feelings for the rest of 2019, all 16 have a target for euro strength in 2020’s first half. That seems lopsided, especially since there is no clarity on what happens when European Central Bank (ECB) president Mario Draghi passes the scepter to Christine Lagarde this winter.

Figure 2: Street Consensus, EUR

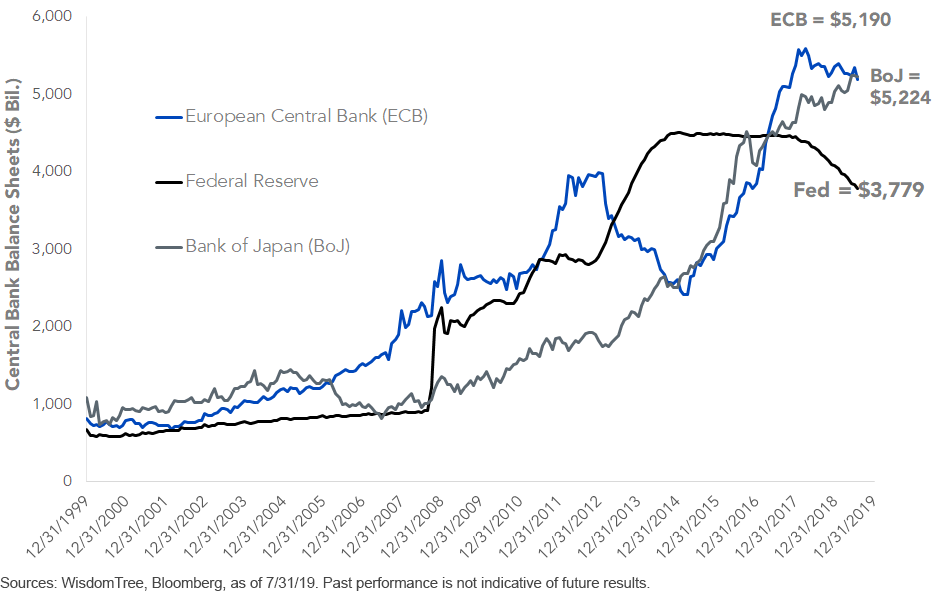

We’re coming up on nine years since Guido Mantega, the former Brazilian finance minister, coined the term “currency wars.” The ECB and the Bank of Japan have been at it ever since, but I argue the Federal Reserve (Fed) stopped fighting hard in 2015, rolling its once-$4.5 trillion balance sheet to $3.8 trillion (figure 3).

Figure 3: Currency Wars

Not to worry, U.S.-domiciled readers who desire dollar debasement. The Fed may be fighting the currency war meekly, but Washington makes up for it. President Trump is clearly jawboning for a weak dollar. There’s also the matter of the federal fiscal situation, which doesn’t matter—until it matters. The U.S. budget deficit-to-GDP ratio of 4.3% is the reddest ink in the G10.

Put it together and we have a state of “total” currency war, though when Mantega looked at the 2010 scene, those battles had a backdrop of severe societal panic. But in 2019, with the S&P 500 just a few percentage points below highs put in north of 3,000? Hardly.

That’s why the saga’s next possible chapter, which is equity positive and euro negative, is particularly surreal: ECB purchases of stocks.

It took less than a generation to balloon the ECB’s balance sheet from below €1 trillion to €4.69 trillion (US$5.19 trillion) via bond purchases. How big of a dent can the ECB make in equities? This isn’t the $24 trillion S&P 500; the MSCI EMU Index is worth only €3.77 trillion ($4.18 trillion).

Did you know the Swiss National Bank had 20% of its reserves in global equities in the first quarter? Russia is on a similar wavelength, though its taste is for gold; that hoard is up to $100 billion from $50 billion four years ago. Washington placed sanctions on Moscow, so Moscow diversified. Trying to figure out how the metal got to $1,500 an ounce? China is accumulating.

It’s not just a handful of players that have “gone rogue” in the once staid world of central banking. South Africa and Israel have also played the something-other-than-bonds game. We cannot leave out the mad scientist of central bank experimentation: the Bank of Japan. It has been buying equity exchange-traded funds for a half decade. Its published guidance from last summer was for ¥5.7 trillion of yearly purchases. That equates to €48 billion. If the ECB plays Simple Simon, that buys 1% of European stocks each year.

If we see several years of this, guess who becomes the dominant owner of equity capital? Ah, control of the means of production by an unelected, opaque, centralized power. Moral hazard, shmoral shmazard.

Lucky for us, the critical mass is still years into the future. Love it or hate it, this looks like a “don’t fight the Fed” situation, only this time the player is the ECB.

Unless otherwise stated, data source is Bloomberg, as of August 7, 2019.