Let’s Talk about Hyman Minsky

The recent failures at Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank (SBNY) and Credit Suisse (CS) reintroduced some terms back into the news and social media postings that we haven’t heard much since the great financial crisis (GFC) back in 2008–2009: “systemic risk,” “moral hazard,” “lender of last resort” and “risk management.”

We’ve also been reintroduced to Hyman Minsky. So, who was he, and why do we care?

Minsky was a late-20th-century economist who was not especially renowned or acclaimed until late in his lifetime (he died in 1996). His primary contribution to economic thought was his research into and explanation of financial crises, summarized in his working paper, “The Financial Instability Hypothesis.”1

While only 10 pages in length and with no equations, this paper was nonetheless seminal in its own way, finally gathering the attention it deserved during the GFC, especially in a brilliant article by Edward Chancellor in Institutional Investor magazine, published in February 2007 and titled “Ponzi Nation.” It would be difficult to explain in more accessible terms what was about to happen in the GFC.2

In Minsky’s own words, he believed, “Instability is an inherent and inescapable flaw of capitalism.” Specifically, he segmented borrowers into three categories:

1. Hedge borrowers, whose cash flow can cover both interest and principal on any debt incurred.

2. Speculative borrowers, whose cash flow can cover interest but not principal.

3. Ponzi borrowers, whose cash flow cannot cover either interest or principal and who must rely on rising asset prices and increased borrowing to survive (sound familiar?).

Minsky’s theory states that in strong economic times, the risk of failure is “forgotten,” leading to increased borrowing and a slow (but inevitable) “flow” from hedge borrowing through speculative borrowing and, finally, to Ponzi borrowing, at which point a market bubble has evolved that will soon, just as inevitably, pop.

In other words, periods of seeming market stability mask increasingly high levels of market instability until a “Minsky Moment” is reached—a tipping point when the asset or credit bubble pops, the leveraged house of cards collapses and financial markets crater.

It would be hard to find a more elegant or accurate description of the events leading up to and through 2008 and early 2009. It also helps to explain why so many investors did not see—or chose to ignore—the warning signals that preceded that destructive market collapse; as a collective body, investors forgot that failure was an option.

So, why is Minsky’s name being tossed around these days?3 On the surface, the failures at SVB and SBNY—both smallish to medium-sized banks—do not seem to pose a broader systemic risk to the U.S. or global banking system. We guess one could argue that the “runs” on those two banks resulted in panic at Credit Suisse, which had been suffering deposit and investor “bleed” for months anyway over a variety of business model decisions, and perhaps catalyzed its final collapse into the arms of UBS.

With respect to SVB, the primary problem seems to have been, simply, bad risk management of its balance sheet. The vast majority of its deposits (most of which were uninsured by the FDIC) were theoretically being hedged by holding long-dated U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities—both with seemingly low credit risk but by no means free of duration risk. As interest rates rose over the past several months, the value of that collateral fell accordingly—again, no big deal if the securities did not default and could be held to maturity and redeemed at face (par) value.

But, as investors withdrew their deposits, SVB had to sell those “hedge assets” at ever-increasing losses to match the withdrawal requests, which created a classic “run on the bank,” exacerbated by mobile phone banking apps that make withdrawals and transfers almost instantaneous these days. George Bailey never had to deal with that during the bank run on Bailey Building & Loan in the time of “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

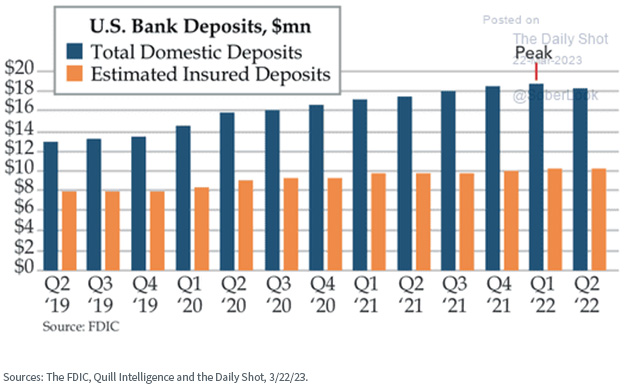

Take a look at the next two charts. The first shows the level of uninsured assets across the banking industry (that is, deposits in excess of FDIC limits).

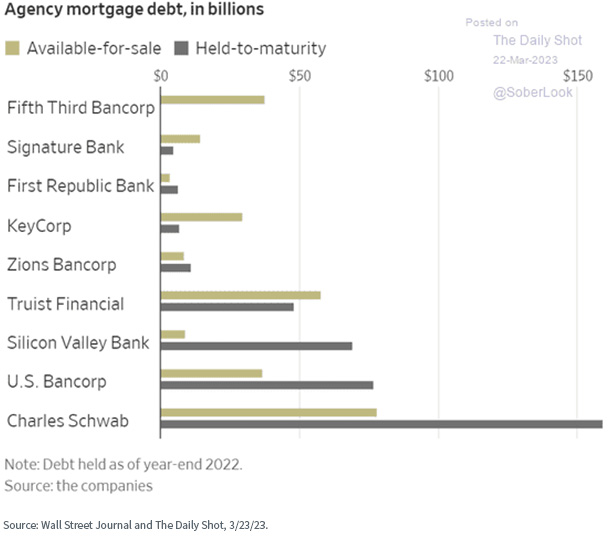

Now, look how mismatched SVB was with respect to “available-for-sale” assets (assumed to be highly liquid to meet deposit withdrawal demands under “normal” market conditions) versus “held-to-maturity” assets (in this chart measured in mortgage-backed securities, most of which, along with U.S. Treasuries, were thought to be “safe” capital)—once the bank run began, it never stood a chance of surviving without a massive bailout.

So, why did SVB find itself in such a dilemma? One reason is that almost ALL banks engage in duration mismatching—they take in short-term deposits for which they pay low rates of interest and then lend the money back out longer-term at higher rates to individual and commercial borrowers. The difference between the two rates is the primary way banks make money—the so-called “net interest margin” (NIM). Few banks, however, leave themselves as exposed to rate mismatches as SVB did.

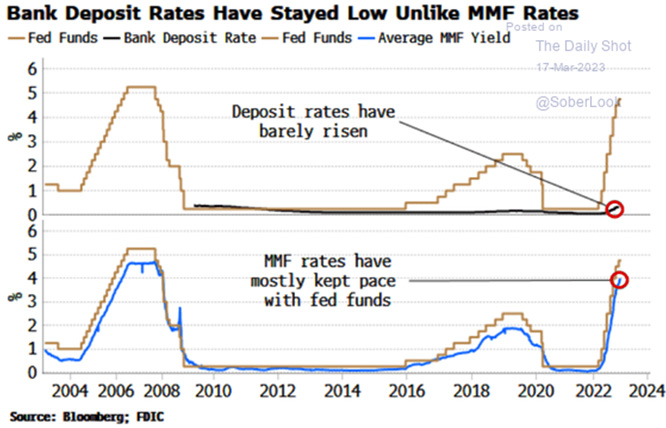

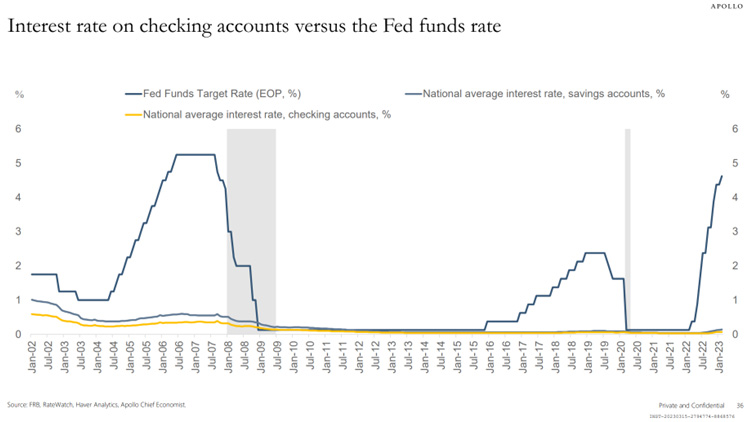

And why not? This is where Fed policy and perhaps other political considerations come in. For most of the past 10 years, short-term rates essentially were pegged near zero, so banks had no reason not to pay very low deposit rates. But as they attempted to optimize their NIM, they did not raise deposit rates as the Fed Funds Rate increased following months of hawkish Fed action.

Investors responded accordingly—regardless of any concern over bank solvency, why NOT consider moving short-term money to potentially higher-yielding money market and other similar solutions especially if those deposits exceeded the FDIC cap. As an example, our own floating rate Treasury product, USFR, saw tremendous net inflows in 2022 and so far in 2023. Both of the following charts were sourced from The Daily Shot on Friday, March 17, 2023.

For definitions of terms in the chart above, please visit the glossary.

For definitions of terms in the chart above, please visit the glossary.

Conclusions

All of this brings us back to Hyman Minsky. Frankly, it is too early to tell if the current banking “crisis” will spread and present “systemic risk” to the U.S. and global economies. Certainly, the political and policy responses so far have thrown “moral hazard” to the wind (rescuing institutions from their own mistakes and thereby encouraging them to repeat them in the future in the belief they will get bailed out—again) in an attempt to prevent a “Minsky Moment” meltdown.

It can be dangerous to overreact in volatile times, in either direction—fear or greed. We continue to believe that focusing on quality companies, sustainable dividend payers and lower-risk fixed income solutions charts an appropriate course through what may become increasingly stormy seas.

1 https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp74.pdf.

2 https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b150nxg9wbtc22/ponzi-nation.

3 See, for example, “JPMorgan’s Kolanovic Sees Increasing Chances of ‘Minsky Moment,’” TheWealthAdvisor.com, 3/21/23: https://www.thewealthadvisor.com/article/jpmorgans-kolanovic-sees-increasing-chances-minsky-moment.

Important Risks Related to this Article

There are risks associated with investing, including the possible loss of principal. Securities with floating rates can be less sensitive to interest rate changes than securities with fixed interest rates but may decline in value. The issuance of floating rate notes by the U.S. Treasury is new, and the amount of supply will be limited. Fixed income securities will normally decline in value as interest rates rise. The value of an investment in the Fund may change quickly and without warning in response to issuer or counterparty defaults and changes in the credit ratings of the Fund’s portfolio investments. Due to the investment strategy of this Fund, it may make higher capital gain distributions than other ETFs. Please read the Fund’s prospectus for specific details regarding the Fund’s risk profile.