Dividends: Traditional vs. Behavioral Finance

A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.1

In investing, this describes investors’ preference for dividends (the bird in the hand) relative to future price appreciation (two in the bush).

While this preference is undeniable, the impact of dividends on company valuation represents a fault line between a traditional finance view and a behavioral finance view of markets:

- From a traditional finance standpoint—where all investors are rational and markets efficient—the relevance of dividends on firm valuation can be tenuous because investors should be indifferent between dividends and capital gains.

- A behavioral finance perspective gives license to the impact of dividends on firm value because investors may prefer firms that pay dividends, assigning value to a steady payout and thus increasing the value of these companies.

To get a sense of how much investors care about dividends, consider this: according to Bank of America Research, 46% of actively managed equity fund assets is in yield-focused funds, up from less than 20% in 2010.2

In short, investors—both professional and retail—care about dividends. A lot.

Modigliani-Miller and Dividend Irrelevance

Franco Modigliani and Merton Miller both won Nobel prizes in part for their “dividend irrelevance” theory.3 The theory states that firms that pay more in dividends will have less price appreciation, resulting in the same total return to shareholders regardless of dividend payout.

While the Modigliani-Miller Model has several assumptions that don’t necessarily hold up in a real-world setting (no taxes or trading costs, to name two), the creakiest assumption is that investors are indifferent between dividends and price appreciation.

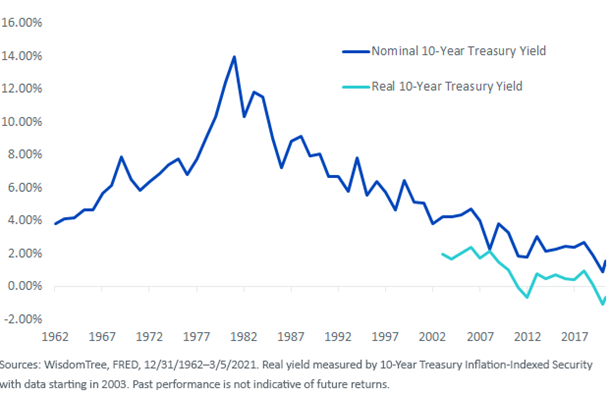

Since their theory was published in the early 1960s, there have been profound changes in interest rates and demographics that have accelerated investor demand for cash dividends.

In 1962, the nominal 10-Year Treasury yield was around 4%. The nominal 10-Year government yield today is around 1.60% and the real yield is negative 60 basis points.

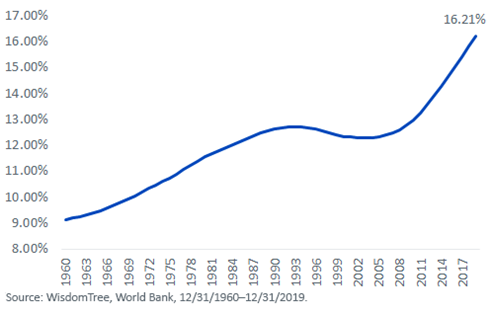

In 1960, 9% of the population was above 65. In 2019, that portion of the US population was 16% and steadily climbing each year with the aging of Baby Boomers.

% of US population above 65

The population today has a greater percentage of retirement-aged individuals, and inflation-adjusted rates on government Treasuries are negative. This paradox means there are more retired investors with passive income needs at a time when fixed income returns after inflation may be negative.

But what about the notion that investors can sell an equivalent of shares to manufacture their own dividend?

Richard Thaler and Mental Accounting

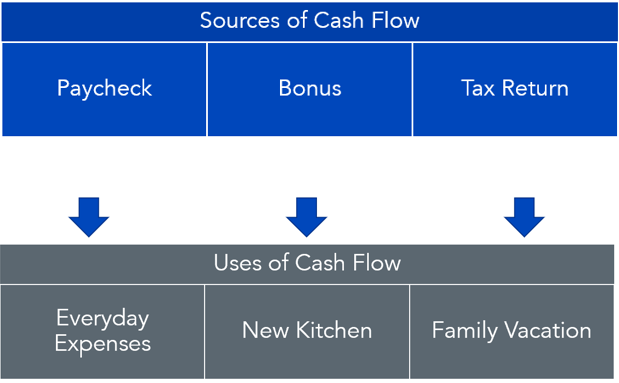

While traditional finance tells us that money is fungible and all cash flows should be viewed as one account, almost everyone uses some mental bucketing with their cash inflows and outflows.

Richard Thaler won the 2017 Nobel Prize for his research into behavioral economics, which included the study of what is called mental accounting.4

Most people use mental accounts (or buckets) to guide their financial decisions. While this isn’t perfectly rational, these heuristics are how humans make sense of complex life decisions.

For many retirees, when their main source of cash flow —a paycheck—goes away, it is replaced by the steady, recurring income received from dividends and interest in a retirement account.

Mental Accounting Example

The Dividend Anomaly

So, dividends matter to investors—perhaps now more than ever—even if purely academically speaking a dividend can be manufactured by selling shares.

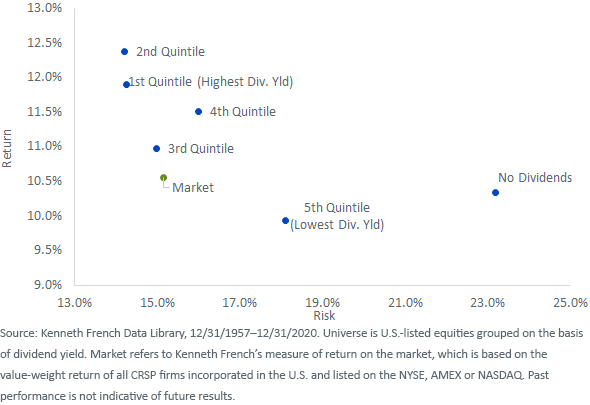

When looking at the long-term returns and volatility of dividend payers, it is also clear that an anomaly exists in the outperformance and lower volatility of higher dividend payers relative to companies that pay low or no dividends at all.

Traditional finance theory would say there is no justification for this anomaly to persist:

- Remember, dividends should be irrelevant to investors versus capital appreciation

- Companies with less risk should have lower expected returns

Behavioral finance gives us an alternative theory to support the persistence of this outperformance:

- Empirically, investors do care about dividends

- Loss aversion tells us that investors feel the pain of loss more than the satisfaction of gains. Therefore, when equities are in a drawdown, investors are more likely to hold onto high dividend stocks because they are still receiving the dividend and don’t want to realize a loss.

To be clear—we are not implying that dividends are a free lunch. A dividend paid reduces a company’s cash balance and retained earnings from which future investments are funded.

But what is clear is that over the long run, companies with high dividend yields have offered attractive risk-adjusted returns relative to the broader market, and today’s low-yield environment is creating even greater demand for dividend-focused investing.

Dividend Yield Quintiles (1957-2020)

1The “bird in hand” theory of dividends is attributed to Myron Gordon and John Lintner from the early 1960s. Its detractors refer to it as the “bird in the hand fallacy” as a reminder to investors that a dividend paid should be associated with a price drop.

2Bank of America Research, “How Secure Are Your Dividends?” 4/7/20.

3Merton H. Miller and Franco Modigliani, “Dividend Policy, Growth and the Valuation of Shares,” The Journal of Business, October 1961, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 411-433.

4Thaler, Richard. “Mental Accounting Matters,” 1999, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 12, 183-206.