Currency Hedged Equities – What’s Plain Vanilla?

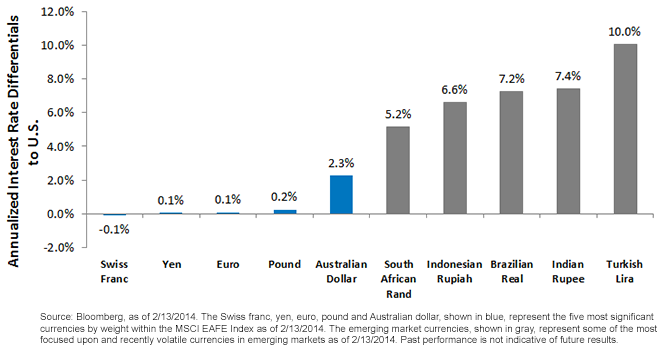

Three currencies—euro, yen and British pound—make up approximately three-quarters of the MSCI EAFE Index weight, and the cost to hedge each of them is less than .25%.3 One might actually get paid something more meaningful to hedge the yen, given that interest rates in the U.S. may increase before those in Japan do, as can be the case if interest rates in an investor’s home country are higher than in the country of the currency being hedged (as is the situation of the Swiss franc; see above).

The bottom line of this cost discussion: currently, the costs are minimal in the developed world and high in some emerging markets. With a practically free option to hedge the risk in Japan and Europe, is it worth taking the risk again for no expected return enhancement in the long run if currency returns are a wash?

What Volatility Reduction?

Vanguard also argued in its report that there is only a marginal benefit to volatility reduction for equities but that currency volatility can dominate fixed income returns, so that is where currency hedging pays, according to them. Recent facts suggests otherwise.

Over the last five years, the volatility to European equities with euro exposure4: 26.2%

Over the last five years, the volatility to European equities5: 18.1%

Volatility contribution of the euro: 8.1%

That is, the euro exposure increased the volatility to European investments for U.S. investors by 8 percentage points. In other words, fully 30% of all the volatility for European equities came from the euro.6 The 30% contribution of total volatility is the same over the last decade (22.9% total volatility, including 6.1% currency volatility).7 I would say that is a meaningful amount of volatility to come from currency risk.

The Case of Japan: Upside Volatility Desired There

Regarding whether hedging currency can increase volatility in certain markets—that certainly has been the case for Japan. In 2013, a declining yen offset appreciating equities and hurt investors from a total return perspective—but one can say those offsetting returns helped lower volatility. Is that the lower volatility investors wanted when accessing Japanese equities? The flows to currency-hedged Japan ETFs suggest investors thought the currency-hedged, local equity-targeting returns were more desirable.

Reframing the Question

The future direction of currencies is tough to predict. This is why I ask: Do you want a secondary currency exposure on top of your local equity returns? If there is little cost to hedge, as there is in Europe and Japan today, you may need significant faith in the euro and the yen if you are going to take that risk unhedged. How many people have such faith in the euro and the yen? My guess is a lot fewer than the number who implicitly take on the risk with traditional, unhedged ETFs.

As one commentator from the Society of Actuaries put it, for most, leaving currency risk unhedged is akin to betting money on coin flips.8

1Karin Peterson LaBarge, “Currency Management: Considerations for the Equity Hedging Decision,” Vanguard Research, September 2010.

2Source: Bloomberg, as of 2/13/2014.

3Source: Bloomberg, as of 2/13/2014.

4European equities with euro exposure: Refers to the returns of the MSCI EMU Index, which is exposed to changes in the exchange rate between the euro and U.S. dollar. Five-year period from 12/31/2008 to 12/31/2013.

5European equities: Refers to the returns of the MSCI EMU Local Currency Index, which is not exposed to changes in the exchange rate between the euro and U.S. dollar. Five-year period from 12/31/2008 to 12/31/2013.

6Sources: MSCI, Zephyr StyleADVISOR, as of 12/31/2013.

7Sources: MSCI, Zephyr StyleADVISOR, as of 12/31/2013.

8Source: Steve Scoles, “Currency Risk: To Hedge or Not to Hedge—Is That the Question?,” Risks and Rewards newsletter, Society of Actuaries, February 2008.

Three currencies—euro, yen and British pound—make up approximately three-quarters of the MSCI EAFE Index weight, and the cost to hedge each of them is less than .25%.3 One might actually get paid something more meaningful to hedge the yen, given that interest rates in the U.S. may increase before those in Japan do, as can be the case if interest rates in an investor’s home country are higher than in the country of the currency being hedged (as is the situation of the Swiss franc; see above).

The bottom line of this cost discussion: currently, the costs are minimal in the developed world and high in some emerging markets. With a practically free option to hedge the risk in Japan and Europe, is it worth taking the risk again for no expected return enhancement in the long run if currency returns are a wash?

What Volatility Reduction?

Vanguard also argued in its report that there is only a marginal benefit to volatility reduction for equities but that currency volatility can dominate fixed income returns, so that is where currency hedging pays, according to them. Recent facts suggests otherwise.

Over the last five years, the volatility to European equities with euro exposure4: 26.2%

Over the last five years, the volatility to European equities5: 18.1%

Volatility contribution of the euro: 8.1%

That is, the euro exposure increased the volatility to European investments for U.S. investors by 8 percentage points. In other words, fully 30% of all the volatility for European equities came from the euro.6 The 30% contribution of total volatility is the same over the last decade (22.9% total volatility, including 6.1% currency volatility).7 I would say that is a meaningful amount of volatility to come from currency risk.

The Case of Japan: Upside Volatility Desired There

Regarding whether hedging currency can increase volatility in certain markets—that certainly has been the case for Japan. In 2013, a declining yen offset appreciating equities and hurt investors from a total return perspective—but one can say those offsetting returns helped lower volatility. Is that the lower volatility investors wanted when accessing Japanese equities? The flows to currency-hedged Japan ETFs suggest investors thought the currency-hedged, local equity-targeting returns were more desirable.

Reframing the Question

The future direction of currencies is tough to predict. This is why I ask: Do you want a secondary currency exposure on top of your local equity returns? If there is little cost to hedge, as there is in Europe and Japan today, you may need significant faith in the euro and the yen if you are going to take that risk unhedged. How many people have such faith in the euro and the yen? My guess is a lot fewer than the number who implicitly take on the risk with traditional, unhedged ETFs.

As one commentator from the Society of Actuaries put it, for most, leaving currency risk unhedged is akin to betting money on coin flips.8

1Karin Peterson LaBarge, “Currency Management: Considerations for the Equity Hedging Decision,” Vanguard Research, September 2010.

2Source: Bloomberg, as of 2/13/2014.

3Source: Bloomberg, as of 2/13/2014.

4European equities with euro exposure: Refers to the returns of the MSCI EMU Index, which is exposed to changes in the exchange rate between the euro and U.S. dollar. Five-year period from 12/31/2008 to 12/31/2013.

5European equities: Refers to the returns of the MSCI EMU Local Currency Index, which is not exposed to changes in the exchange rate between the euro and U.S. dollar. Five-year period from 12/31/2008 to 12/31/2013.

6Sources: MSCI, Zephyr StyleADVISOR, as of 12/31/2013.

7Sources: MSCI, Zephyr StyleADVISOR, as of 12/31/2013.

8Source: Steve Scoles, “Currency Risk: To Hedge or Not to Hedge—Is That the Question?,” Risks and Rewards newsletter, Society of Actuaries, February 2008.Important Risks Related to this Article

There are risks associated with investing, including possible loss of principal. Foreign investing involves special risks, such as risk of loss from currency fluctuation or political or economic uncertainty. Investments focused in Japan and Europe are impacted by the events and developments associated with the region, which can adversely affect performance. Investments in emerging, offshore or frontier markets are generally less liquid and less efficient than investments in developed markets and are subject to additional risks, such as risks of adverse governmental regulation and intervention or political developments. Investments in currency involve additional special risks, such as credit risk and interest rate fluctuations. Derivative investments can be volatile, and these investments may be less liquid than other securities, and more sensitive to the effects of varied economic conditions. Fixed income investments are subject to interest rate risk; their value will normally decline as interest rates rise. Fixed income investments are also subject to credit risk, the risk that the issuer of a bond will fail to pay interest and principal in a timely manner, or that negative perceptions of the issuer’s ability to make such payments will cause the price of that bond to decline. As certain funds can have a high concentration in some issuers, those funds can be adversely impacted by changes affecting those issuers. Due to the investment strategy of certain funds, they may make higher capital gain distributions than other ETFs. Please read the Fund’s prospectus for specific details regarding the Fund’s risk profile. Investments in emerging, offshore or frontier markets are generally less liquid and less efficient than investments in developed markets and are subject to additional risks, such as risks of adverse governmental regulation and intervention or political developments. ALPS Distributors, Inc., is not affiliated with Vanguard.

Jeremy Schwartz has served as our Global Chief Investment Officer since November 2021 and leads WisdomTree’s investment strategy team in the construction of WisdomTree’s equity Indexes, quantitative active strategies and multi-asset Model Portfolios. Jeremy joined WisdomTree in May 2005 as a Senior Analyst, adding Deputy Director of Research to his responsibilities in February 2007. He served as Director of Research from October 2008 to October 2018 and as Global Head of Research from November 2018 to November 2021. Before joining WisdomTree, he was a head research assistant for Professor Jeremy Siegel and, in 2022, became his co-author on the sixth edition of the book Stocks for the Long Run. Jeremy is also co-author of the Financial Analysts Journal paper “What Happened to the Original Stocks in the S&P 500?” He received his B.S. in economics from The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and hosts the Wharton Business Radio program Behind the Markets on SiriusXM 132. Jeremy is a member of the CFA Society of Philadelphia.