They say every bull market needs to scale a wall of worry, and late last week, further evidence was added to this truism: a possible $500 million default by a Chinese investment trust that was distributed to investors by a state-owned bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC). The tremor reverberated outside China because a Chinese banking crisis that spreads outside its borders is the type of exogenous shock that could put an end to both the global economic recovery and the bull market in stocks. However, I don’t believe this is the butterfly that starts a Shanghai tsunami. Over the weekend, news broke that investors in the trust would, in effect, be bailed out, reversing the ICBC’s initial position that the investors in the trust would be responsible for any losses.

Chinese authorities could have used the pending default as a teaching moment to instruct investors on the meaning of the phrase “moral hazard.” But the interests of the Chinese government are broader than just maximizing profits for the shareholders of a single company. Chinese government officials need to rein in the excesses of China’s multi-trillion dollar

shadow banking system while also maintaining economic growth and social stability. With

credit spreads widening and China’s Central Bank working hard to keep its interbank lending system

liquid, Chinese authorities have little upside in letting outraged investors, who thought their investment came with

downside protection, hold 100% of the proverbial bag, particularly if their investment capital, collectively through such trust offerings, helps China’s more speculative companies expand. So some combination of the financial institutions or local governments involved, and not the wealthy private banking clients who bought into the trust, will end up shouldering the loss. Odds are there will be more investment trusts that face similar resolutions. So given this precedent, Chinese banks will likely bear more of the burden for “trust” liabilities that would normally sit on the balance sheets of private investors.

The flare-up in China is a reminder of how interconnected the global financial system and, therefore, the global economy are. The real risk in China is the “true” quality of the loans on the books of the banks that were made to help fuel China’s investment-led growth over the past decade. In a slowing economy, and certainly in a recession, defaults rise, particularly among construction, real estate development and operating companies that embarked on projects when access to credit and expectations for growth were much greater. If those loans remain on the books of the Chinese banks, recessionary write-downs of such non-performing assets could trigger a huge margin call on China’s credit-led expansion. At least that’s how things work when market forces are allowed to roam free in a capitalist economy. Like the Greek Furies, the cyclical gods of capitalist economies use market downturns to hunt down and punish those who took excessive risks, often killing companies not strong enough to survive the full business cycle. But China is an opaque, mixed economy, with key parts of its largest economic actors owned by the state. It’s hard to evaluate China as a risk when we don’t have insight into the quality of the loans on its banks’ books. Nor do we know what a recession looks like in China, or how the government would respond if the credit bubble were to burst. There is no savings & loan (S&L) crisis, or systemic banking crisis, we can point to as a precedent. There’s just an economic expansion that’s in its third decade—leaving many to wonder: when and how will it end? Or is China so efficiently run, and its capital so elegantly allocated, that we need not worry about excesses that normally afflict economies at the end of business expansions?

Ever since China entered the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 and integrated itself into the global economy, it hasn’t experienced what we would call a normal recession. Annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth in China has never dipped below 6% since then, and even now, with an $8 trillion economy, it continues to grow at 7%, according to government reports. But, even though China has been the world’s fastest-growing major economy since December 31, 2001, China’s equity market, as measured by the

Shanghai Composite Index, has dramatically underperformed the broader

MSCI Emerging Markets Index. China’s stock market has returned just 6.7% per year from 2001 through the end of 2013, underperforming the MSCI EM benchmark in U.S. dollars by 6 percentage points per year on an annualized basis. We may now be seeing the long-term effects of State ownership of publicly traded enterprises.

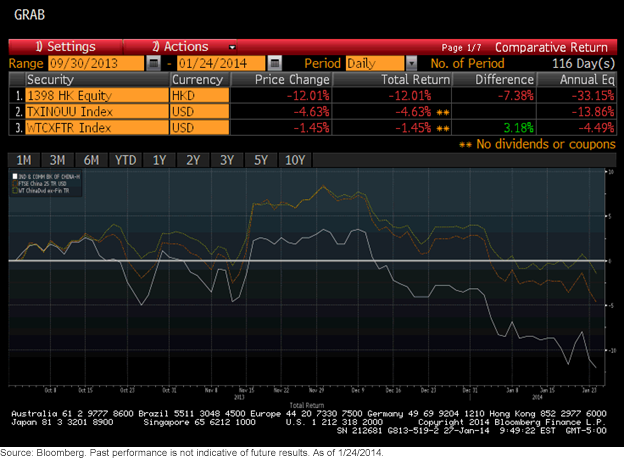

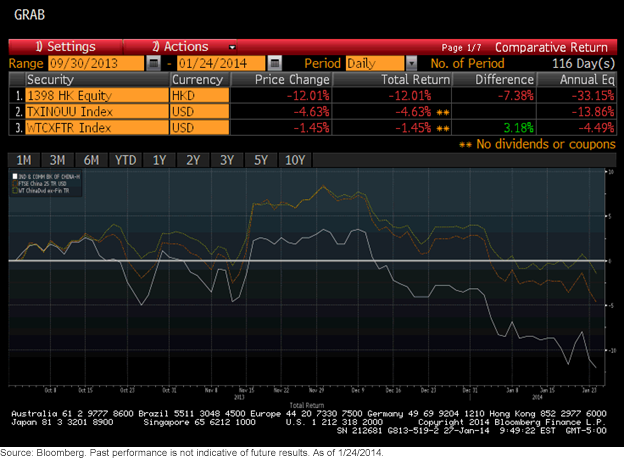

The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China is typically one of the larger holdings in most emerging market baskets. It represents nearly 7% of the weight of the FTSE China 25 Index. The chart below shows how the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (in white) (Ticker 1398: HK) has sold off over the past few months, and how the weakening of financial stocks have also impacted the

FTSE China 25 Index (in orange) (TXINOUU), 55% of which comprises stocks in the financial sector. By comparison, the

WisdomTree China Dividend Ex-Financials Index (WTCXFTR), which measures the performance of Chinese dividend paying stocks outside the financial sector (in yellow), has declined just 1.5% since September 30, 2013:

Click here for standardized Index performance.

Click here for standardized Index performance.

The risk of a potential banking crisis in China remains. But it is a risk, like the risk presented by the San Andreas Fault in California, without a specific timeframe. Financial markets meander through each day, knowing that one day the “big one” may hit. We just don’t know when. In the interim, with uncertainty over how China will navigate a soft landing,

P/E multiples on many Chinese companies and on the Chinese equity market will likely remain depressed. Further bad news out of China relating to trust defaults will likely impact the volatility of stocks in the U.S. Assuming such rumblings stop short of a full-blown credit crisis, I believe any short-term correction in U.S. stocks will mark another buying opportunity for long-term investors in U.S. equities.

In the next weeks, in Part II of this blog post, I’ll explore the three reasons why I believe the bull market in U.S. stocks still has legs.

Important Risks Related to this Article

Investments focused in China are increasing the impact of events and developments associated with the region, which can adversely affect performance. Foreign investing involves special risks, such as risk of loss from currency fluctuation or political or economic uncertainty.

Click here for standardized Index performance.

The risk of a potential banking crisis in China remains. But it is a risk, like the risk presented by the San Andreas Fault in California, without a specific timeframe. Financial markets meander through each day, knowing that one day the “big one” may hit. We just don’t know when. In the interim, with uncertainty over how China will navigate a soft landing, P/E multiples on many Chinese companies and on the Chinese equity market will likely remain depressed. Further bad news out of China relating to trust defaults will likely impact the volatility of stocks in the U.S. Assuming such rumblings stop short of a full-blown credit crisis, I believe any short-term correction in U.S. stocks will mark another buying opportunity for long-term investors in U.S. equities.

In the next weeks, in Part II of this blog post, I’ll explore the three reasons why I believe the bull market in U.S. stocks still has legs.

Click here for standardized Index performance.

The risk of a potential banking crisis in China remains. But it is a risk, like the risk presented by the San Andreas Fault in California, without a specific timeframe. Financial markets meander through each day, knowing that one day the “big one” may hit. We just don’t know when. In the interim, with uncertainty over how China will navigate a soft landing, P/E multiples on many Chinese companies and on the Chinese equity market will likely remain depressed. Further bad news out of China relating to trust defaults will likely impact the volatility of stocks in the U.S. Assuming such rumblings stop short of a full-blown credit crisis, I believe any short-term correction in U.S. stocks will mark another buying opportunity for long-term investors in U.S. equities.

In the next weeks, in Part II of this blog post, I’ll explore the three reasons why I believe the bull market in U.S. stocks still has legs.